Opioid overdoses are still a serious problem, even with recent improvements. In 2024, the United States recorded 80,391 overdose deaths, and 54,743 of those involved opioids. Synthetic opioids like fentanyl remain a major cause. These numbers show how important it is to know how to respond during an emergency.

Learning how to recognize an overdose and act fast can save a life. This is why getting your BLS Certification from CPR Select matters. The course teaches you how to perform high-quality CPR, use an AED, and respond confidently during an opioid overdose until help arrives.

What Are Opioids?

Opioids are central nervous system depressants that relieve pain and cause sedation. They work by binding to opioid receptors in the brain and spinal cord, blocking pain signals and slowing certain body functions, including breathing.

How Opioids Work?

Opioids attach to mu, delta, and kappa receptors, reducing nerve activity and lowering the release of neurotransmitters. This produces pain relief, relaxation, and, at high doses, respiratory depression, which is the main danger in overdoses.

What are the Types of Opioids?

Opioids come in different forms and have different uses. Understanding the type helps responders know the likely effects, risks, and proper emergency response.

- Prescription Opioids: These include morphine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, and methadone. They are legally produced and used under medical supervision to manage pain.

- Illicit Opioids: These include heroin and illegally made fentanyl and its analogs. They are unregulated, often mixed with other substances, and are involved in most fatal overdoses.

How Opioids Affect the Body?

Opioids work by binding to nervous system receptors. This alters nerve signaling and depresses the central nervous system, reducing alertness and affecting vital functions like breathing and consciousness.

What are the Respiratory Effects of Opioids?

Opioids depress the brainstem respiratory centers. This slows and shallows breathing, lowers the response to rising carbon dioxide and low oxygen, and can lead to hypoxemia and hypercapnia. Reduced breathing can threaten airway patency and tissue oxygen delivery.

Opioids also alter consciousness, cardiovascular function, and gastrointestinal motility. For example:

- Mu receptor activation slows intestinal movement, causing constipation.

- Reduced sympathetic activity can lead to bradycardia and low blood pressure.

What are the Factors That Change Effects?

The impact of opioids depends on:

- Dose and exposure

- Tolerance or receptor sensitivity

- Other sedatives (alcohol, benzodiazepines)

- Age or chronic health conditions

These factors can make respiratory depression worse. Tolerance to pain relief develops faster than tolerance to breathing suppression.

Reversing Effects

Naloxone blocks opioid receptors and can restore breathing quickly. Large doses or long-acting opioids may need repeated administration and monitoring.

Receptor activity explains both immediate effects and possible long-term changes in drug responsiveness. Understanding this helps responders anticipate risks and plan interventions.

What Are the Chemical Categories of Opioids?

Opioids can be grouped by their chemical structure and origin. Understanding these categories helps emergency responders recognize the substance involved and anticipate potential risks.

- Natural / opium-derived opioids: Extracted from the opium poppy, e.g., morphine and codeine. Usually predictable effects like respiratory depression and pinpoint pupils.

- Semi-synthetic opioids: Chemically modified from natural opiates, e.g., oxycodone, hydrocodone, and heroin. Often more potent and faster-acting.

- Fully synthetic opioids: Fully lab-made, e.g., fentanyl, methadone, sufentanil, and fentanyl analogs. Can be extremely potent and may require multiple naloxone doses.

- Prescription medical formulations: Manufactured for clinical use, e.g., immediate- or extended-release tablets, transdermal patches. Dose and formulation affect toxicity and monitoring needs.

- Illicit synthetically modified derivatives: Produced illegally, often contaminated or mixed with other drugs. Effects are unpredictable, and naloxone response may be variable.

- Mixed-action or atypical opioids: Opioids with additional mechanisms, e.g., tramadol and tapentadol. Can cause atypical presentations like seizures or serotonin syndrome.

Knowing these chemical categories supports rapid assessment, guides naloxone administration, and improves airway management in opioid emergencies. It also helps responders anticipate complications based on potency and formulation.

What Are the Medical Uses of Opioids?

Opioids are medications used to relieve moderate to severe pain. They help patients manage pain quickly, support procedures, and improve comfort in palliative care. Opioids work by binding to opioid receptors in the nervous system to reduce pain perception.

Key Medical Uses of Opioids:

- Acute pain in emergency settings: Rapid pain relief in trauma or emergency care using IV morphine or fentanyl.

- Chronic pain management: Prescribed in specialty clinics when other treatments are not enough, with careful monitoring.

- Palliative care: Provides comfort for advanced illness, including cancer, heart failure, or COPD, often using oral or parenteral formulations.

- Perioperative and surgical use: Intraoperative analgesia, immediate postoperative pain control, and support for early mobilization.

- Multimodal pain management: Combined with NSAIDs, acetaminophen, regional nerve blocks, physical therapy, or cognitive behavioral therapy for optimal relief.

- Neuropathic pain adjunct: Used with medications like gabapentin or duloxetine when other therapies are insufficient.

Benefits of Opioids

Prompt pain reduction, decreased stress response, improved comfort, and support for rehabilitation or procedures. Pain relief is often measured as at least a 2‑point reduction on an 11‑point scale or a 30% decrease in intensity, which is considered clinically meaningful, according to studies (Farrar et al., 2001, Pain 94:149‑158)

Clinical Considerations

Opioid therapy is tailored to the patient’s needs, comorbidities, and goals. Monitoring may include periodic reassessment, toxicology checks, and naloxone prescription for patients at risk of overdose. Treatment plans should clearly define duration, tapering, and discontinuation criteria.

Opioids play an important role in acute care, chronic pain, palliative care, and perioperative settings. Proper clinical protocols and monitoring ensure safe and effective use.

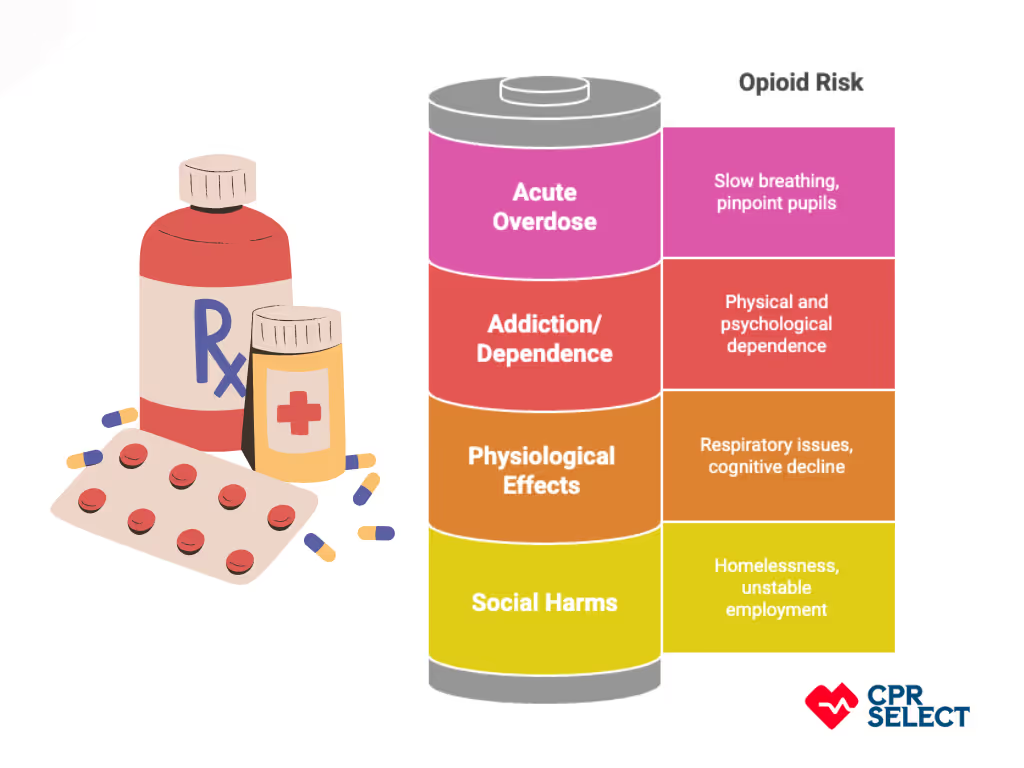

What are the Risks of Opioid Use?

Opioids can help with pain, but they also carry serious risks. These include behavioral, physiological, acute, and social harms. Awareness of these risks is critical for both healthcare providers and emergency responders. Risks of Opioid Use:

- Addiction and Dependence: Repeated opioid use can lead to physical and psychological dependence. Withdrawal signs include sweating, yawning, agitation, abdominal cramps, vomiting, diarrhea, and rapid heartbeat. Responders should ask about recent opioid use and watch for withdrawal when patients are agitated or unstable.

- Tolerance and Escalating Doses: Over time, patients may need higher doses to achieve the same effect, increasing overdose risk. Recent abstinence (e.g., after hospital discharge or incarceration) can make previously tolerated doses dangerous.

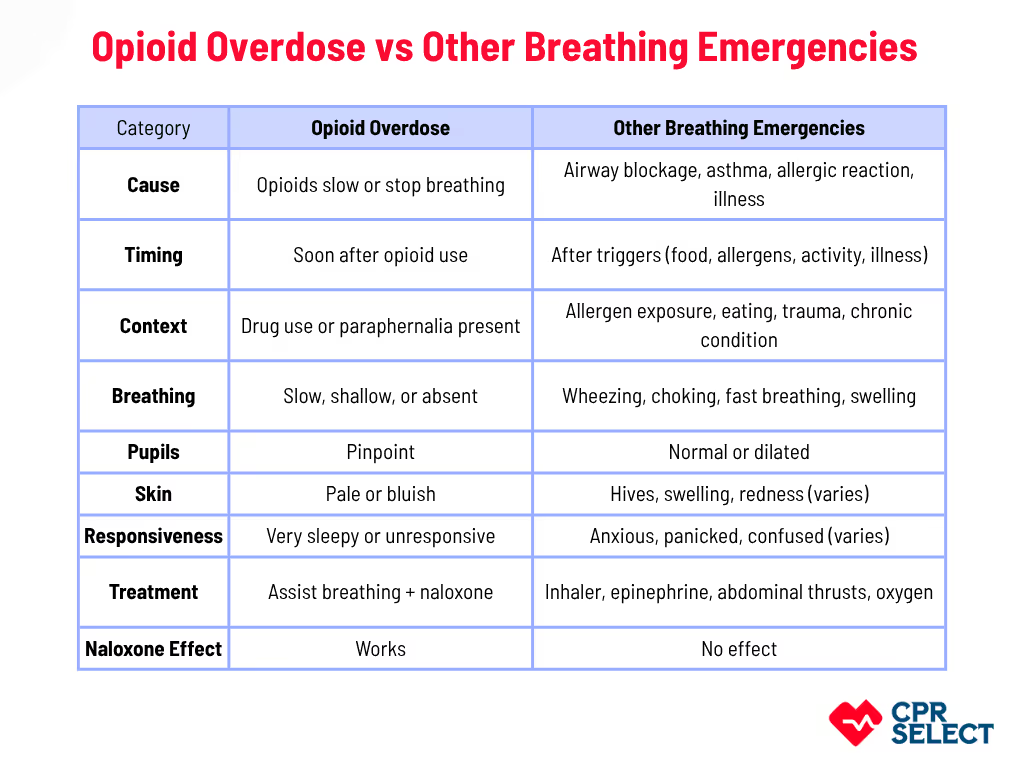

- Acute Overdose Risk: Overdose is a life-threatening emergency. Signs include slow or absent breathing, pinpoint pupils, and depressed consciousness. Immediate airway support and naloxone administration are essential.

- Physiological Side Effects: Chronic opioid use can cause long-term respiratory issues, cognitive decline, or medication interactions. Combining opioids with alcohol or benzodiazepines increases respiratory depression. Responders should monitor oxygen levels and be ready to assist ventilation.

- Social and Functional Harms: Opioid use can lead to homelessness, unstable employment, or unsafe environments. These factors increase emergency calls and complicate scene management. Linking patients to community resources is important when safe.

- Risk Modifiers: Co-use of substances, comorbidities (like COPD or liver disease), potency changes in illicit drugs, and administration method (injection, oral, transdermal) affect overdose severity and response needs. Fentanyl may require repeated naloxone doses.

- Common Misconceptions: Even tolerant patients can experience respiratory arrest. Naloxone is safe and lifesaving, though it may trigger manageable withdrawal. Responders should act promptly.

Opioid use carries multiple interrelated risks: behavioral, physiological, acute, and social. Understanding these risks helps responders anticipate emergencies and plan interventions.