Oxygen administration provides supplemental oxygen to patients who cannot maintain adequate gas exchange. In basic life support, it supports airway management and ventilation by helping stabilize oxygen levels and improve tissue perfusion. Rescuers first secure the airway, ensure effective ventilation, and then add oxygen to reach target saturation levels.

This guide explains when oxygen is needed, the devices used, flow rates, monitoring, and safety precautions. It also highlights why proper training matters because oxygen administration BLS skills are best learned through structured instruction and certification.

What is Oxygen Therapy?

Oxygen therapy is a medical treatment that provides concentrated oxygen to patients who cannot maintain adequate oxygen levels. It restores tissue oxygenation during acute illness and supports vital organs when breathing is compromised. Clinicians choose delivery methods based on patient needs: nasal cannula for low oxygen support, simple face mask for moderate support, and non-rebreather mask for high concentrations during emergencies.

Why Oxygen Therapy Matters in Emergency Care?

Oxygen therapy stabilizes oxygenation, prevents hypoxic injury, and reduces strain on the heart and lungs. Most patients are maintained between 92–96% SpO₂, while those at risk of hypercapnia target 88–92%. Excess oxygen can cause complications, so levels are adjusted carefully with proper equipment monitoring. Overall, oxygen therapy is a critical intervention that protects patients from hypoxia and enhances emergency response.

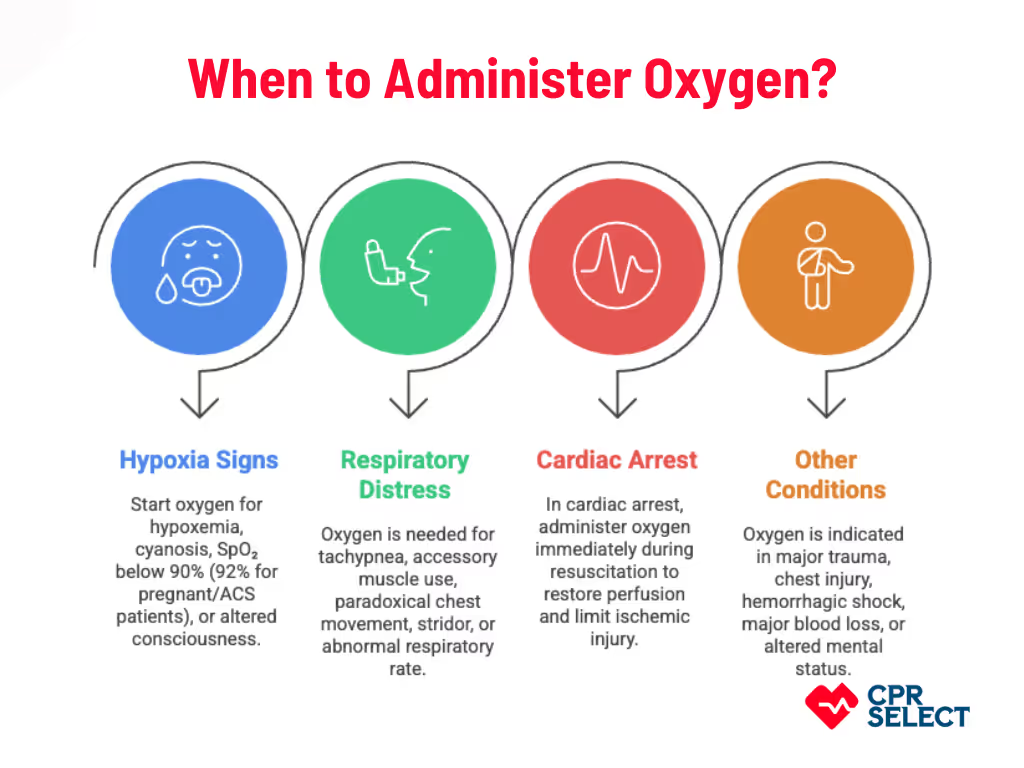

When to Administer Oxygen?

Oxygen should be given when a patient shows acute hypoxia, obvious respiratory distress, cardiac arrest or peri-arrest state, or any urgent condition that reduces oxygen delivery to tissues. The goal is to restore oxygenation and prevent organ injury. This section outlines the specific clinical triggers that guide when to start oxygen therapy.

1. Signs of Hypoxia

Start oxygen when there is clear evidence of hypoxemia. Triggers include central cyanosis, SpO₂ less than 90% at sea level, or less than 92% in pregnant patients or those with acute coronary syndrome. Altered consciousness caused by poor oxygen delivery is also a key indicator.

2. Signs of Respiratory Distress

Respiratory distress itself is a strong indication for oxygen. Look for severe tachypnea, use of accessory muscles, paradoxical chest movement, stridor, or a respiratory rate outside age norms. Oxygen should be started even before confirmatory readings, such as when an adult’s respiratory rate exceeds 30 breaths per minute or when a child shows intercostal retractions.

3. Cardiac Arrest and Peri-Arrest States

In cardiac arrest, oxygen is given immediately as part of resuscitation to restore perfusion and limit ischemic injury. High-concentration oxygen (such as BVM with 100% oxygen) is used when available, and timing is driven by the urgent need to reverse hypoxemia.

Other Acute Conditions

Oxygen is also indicated in major trauma, suspected chest injury, hemorrhagic shock with systolic BP below 90 mmHg, major blood loss, or altered mental status from inadequate oxygenation. Severe asthma or COPD exacerbations with hypoxemia require oxygen titrated to appropriate saturation targets.

When Not to Give Oxygen?

Do not give oxygen to a stable patient with normal SpO₂. Avoid unnecessary high-flow oxygen where hyperoxia may cause harm. For example, in uncomplicated myocardial infarction or acute ischemic stroke without hypoxemia. Oxygen should always be titrated to recommended SpO₂ ranges.

What are the Types of Oxygen Delivery Devices

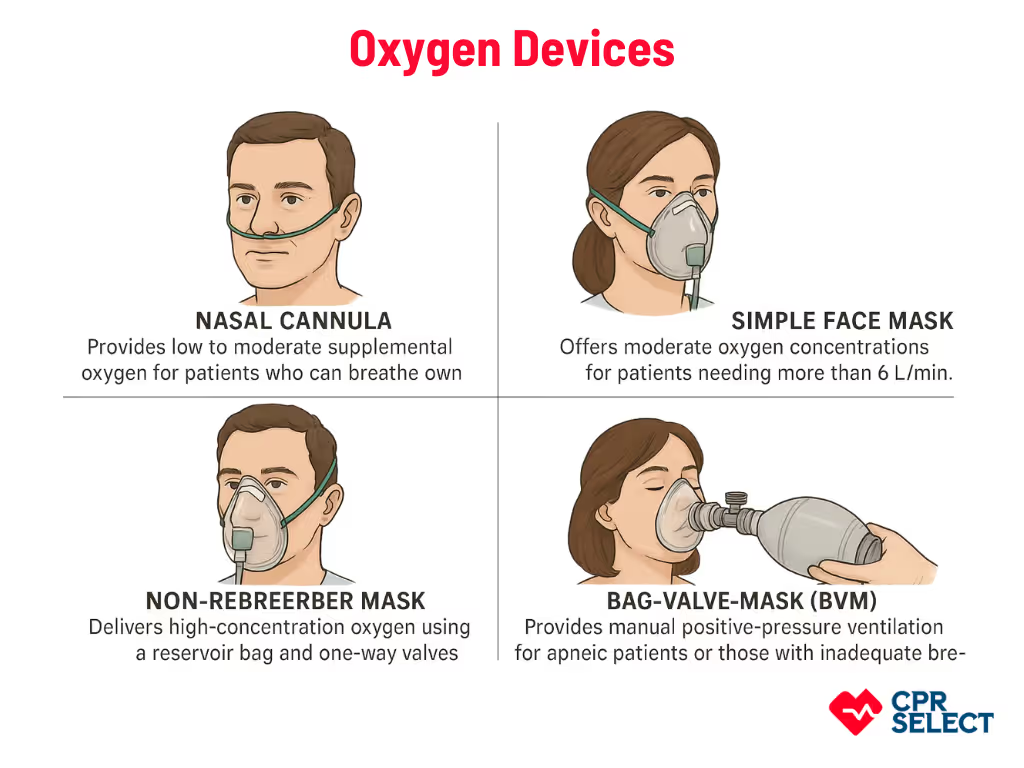

Multiple oxygen delivery devices are available, and clinicians choose them based on the patient’s respiratory status and oxygen needs. These range from low-flow systems to devices used for assisted ventilation.

- Nasal Cannula: Provides low to moderate supplemental oxygen for patients who can breathe on their own. Soft nasal prongs deliver small FiO₂ increases (about 3–4% per 1 L/min). Common in ambulatory care, post-operative recovery, and chronic hypoxemia.

- Simple Face Mask: Offers moderate oxygen concentrations for patients needing more than 6 L/min. Covers the nose and mouth to create a partial oxygen reservoir. Used when work of breathing is increased but high FiO₂ is not yet required.

- Non-Rebreather Mask: Delivers high-concentration oxygen using a reservoir bag and one-way valves to limit room air entry. Requires a tight seal and adequate flow to keep the bag inflated. Used for acute hypoxemia, trauma, or severe respiratory distress.

- Bag-Valve-Mask (BVM): Provides manual positive-pressure ventilation for apneic patients or those with inadequate breathing. Can connect to supplemental oxygen for higher FiO₂. Used in respiratory arrest, severe hypoventilation, and during transport before advanced airway management.

Choosing the right oxygen delivery device depends on the patient’s ability to breathe, required FiO₂, and clinical urgency. Selecting the correct device sets the foundation for safe and effective oxygen administration.

Oxygen Flow Rates

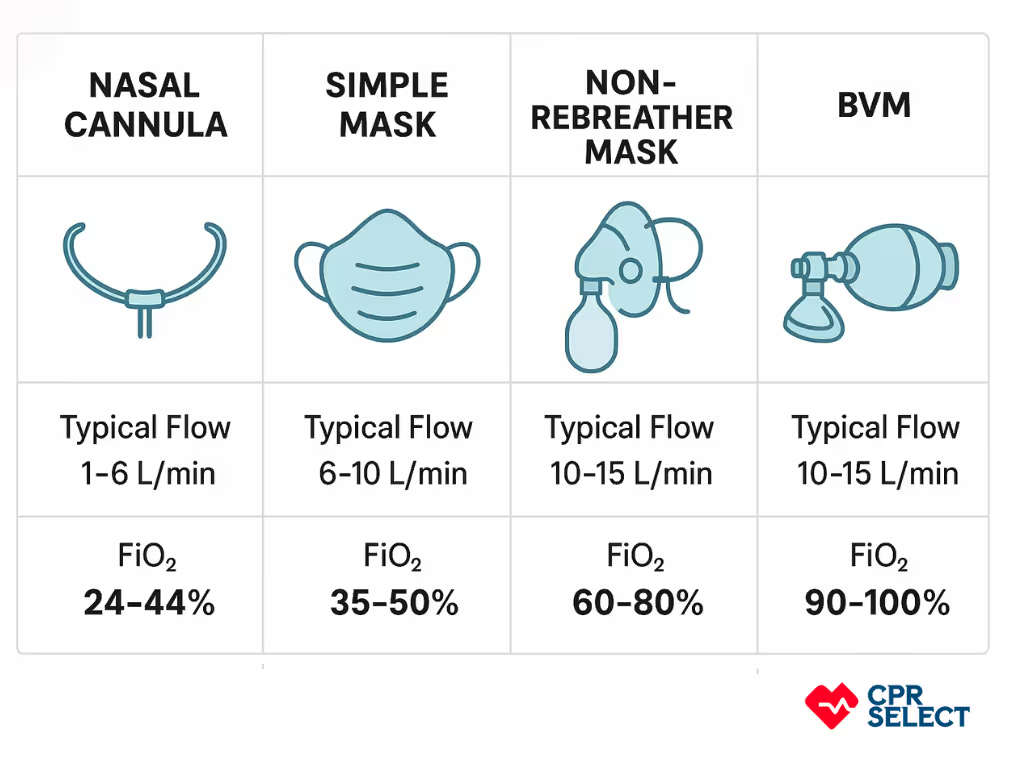

Oxygen flow rate is the amount of oxygen delivered per minute. It depends on the device and patient condition. The goal is to maintain safe oxygen levels while avoiding complications. Clinicians monitor SpO₂ and patient response to adjust flow.

Device-Specific Flow Guidelines:

- Nasal Cannula: 1–6 L/min for mild hypoxemia. Low-flow delivery for adults who can breathe on their own. Monitor SpO₂ and adjust for rapid breathing or mouth breathing.

- Simple Face Mask: 5–10 L/min for moderate oxygen needs. Covers nose and mouth. Avoid flows <5 L/min to prevent CO₂ buildup.

- Non-Rebreather Mask: 10–15 L/min for high oxygen delivery. Uses a reservoir bag and one-way valves. Keep the bag inflated and watch patient breathing.

- Venturi Mask: Manufacturer-specified drive flow (usually ≥15 L/min) for precise oxygen delivery. Best for patients at risk of too much oxygen or CO₂ retention.

- High-Flow Nasal Oxygen (HFNO): 30–60 L/min for adults with severe hypoxemia. Provides humidified oxygen and modest positive airway pressure. Adjust to reduce work of breathing and achieve target SpO₂.

- Pediatric/Infant Oxygen: 0.25–2 L/min via low-flow nasal cannula. Adjust for age and weight. Continuous SpO₂ monitoring required.

- Acute Respiratory Distress or Shock: 10–15 L/min via non-rebreather or 40–60 L/min via HFNO. Watch mental status, heart rate, and oxygen saturation.

- Titration: Adjust flow to meet target SpO₂: 92–96% for most adults, 88–92% for patients at risk of CO₂ retention. Reassess every 5 minutes.

- Special Conditions: Reduce flow for patients with chronic CO₂ retention, post-op risk, or heart failure. Monitor closely and use appropriate devices for controlled oxygen delivery.

Oxygen flow should match the patient’s needs and device capabilities. Continuous monitoring and careful adjustment ensure safe and effective oxygen delivery.