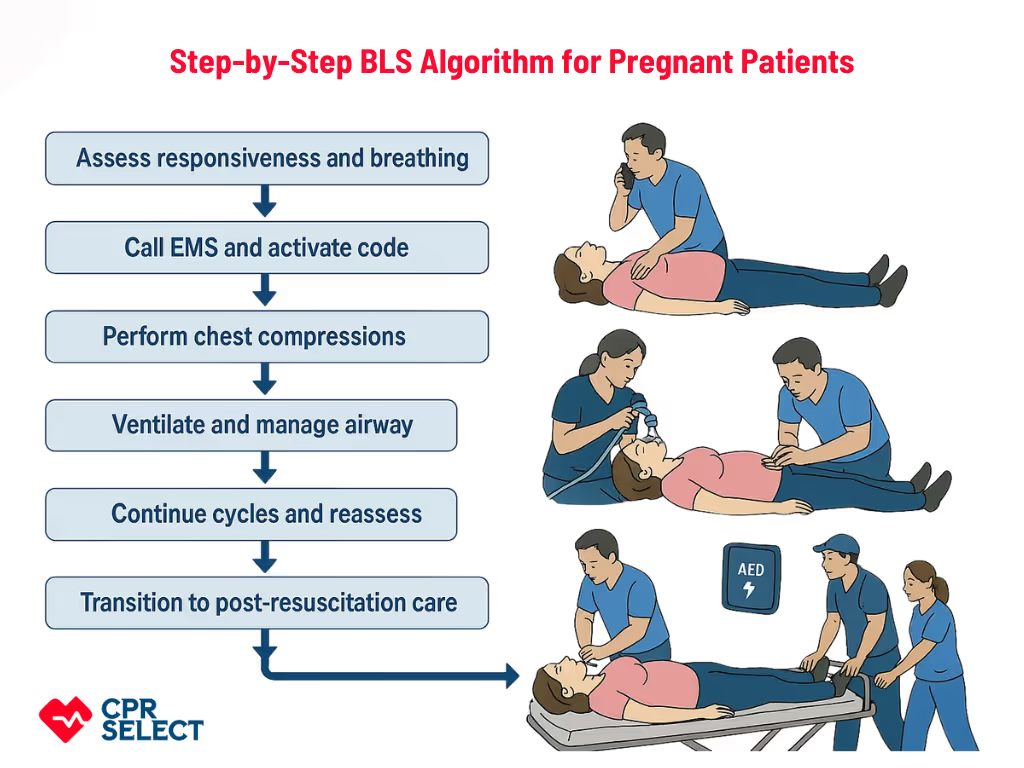

Basic Life Support for pregnant patients adapts standard resuscitation to the physiologic and situational changes of pregnancy, focusing on preserving maternal circulation while considering fetal well being. Pregnancy-specific factors, such as manual left uterine displacement, reduced chest wall compliance, increased blood volume and cardiac output, higher oxygen demand, and the presence of a dependent fetus, affect airway management, ventilation, chest compressions, and resuscitation priorities.

Because maternal circulation is the primary pathway to improving fetal outcomes, BLS for pregnant patients emphasizes restoring effective maternal oxygenation and perfusion first. Responders must understand these core adaptations before learning steps and coordination roles, and specialized BLS training prepares healthcare providers, first responders, trainees, and trained lay rescuers to apply these modifications confidently during emergencies.

Why Basic Life Support Is Critical During Pregnancy?

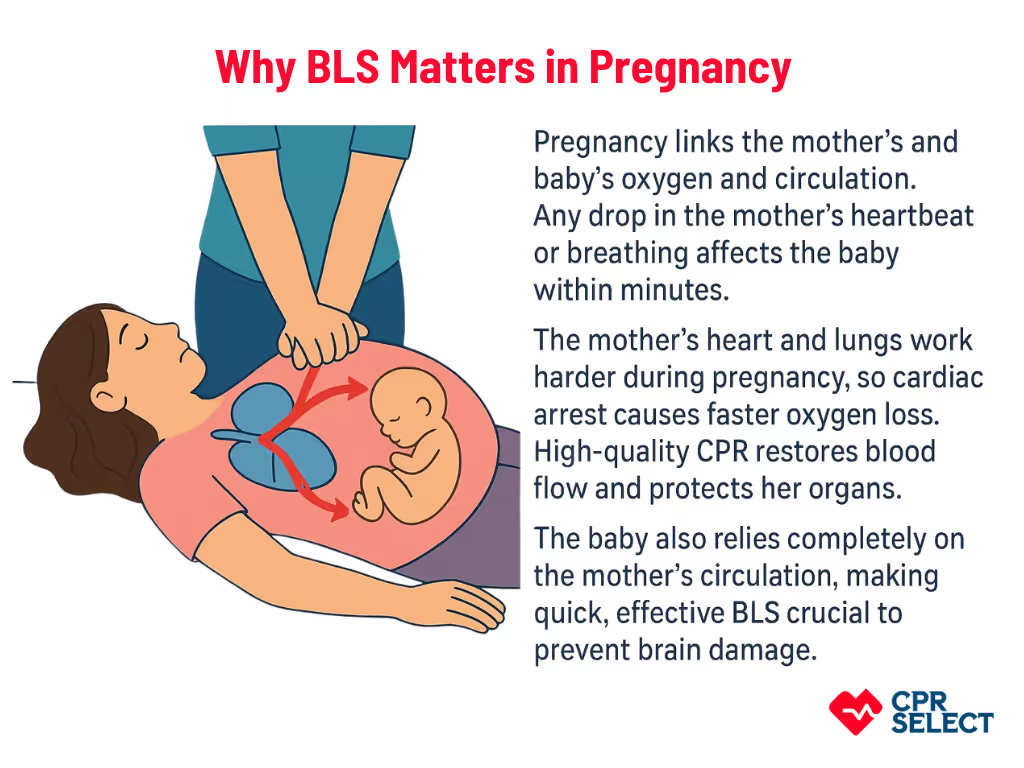

BLS is vital during pregnancy because delays or incorrect actions can quickly harm both the mother and the fetus. Pregnancy creates interdependent maternal–fetal physiology, so any drop in the mother’s circulation or oxygen immediately affects the baby.

- Maternal risks: Pregnancy changes how the heart and lungs work. Blood volume and cardiac output increase by 30–50%. Oxygen needs rise. Lung capacity drops by about 20%. During cardiac arrest, the mother loses oxygen and blood flow fast. This can cause brain injury, heart damage, and organ failure. High-quality CPR helps restore oxygen and circulation and prevents further injury.

- Fetal risks: The fetus fully depends on the mother for oxygen and blood flow. When the mother’s heart or breathing stops, the fetus faces low oxygen, poor placental blood flow, and rising acidity. Restoring the mother’s circulation within 4–6 minutes is critical to prevent fetal brain damage. Effective chest compressions and proper ventilation for the mother directly support the baby.

Maternal deterioration threatens both mother and baby within minutes. BLS for pregnant patients must be prompt, skilled, and adapted to pregnancy.

Why pregnancy changes priorities?

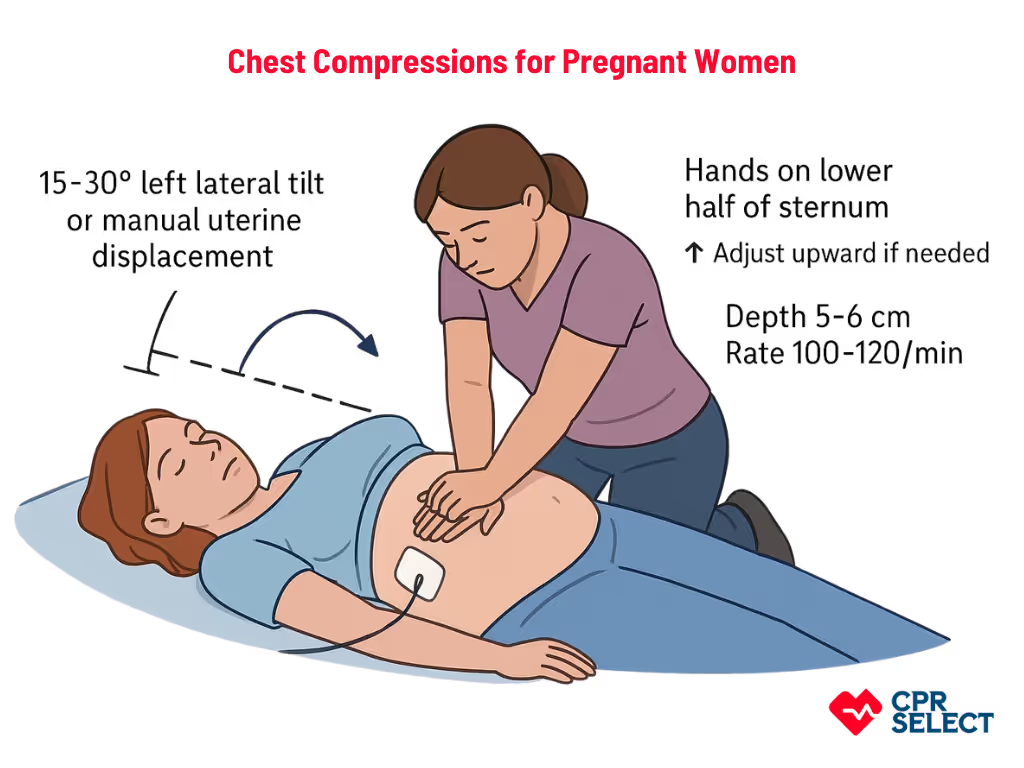

Pregnancy creates a dual-patient emergency. Rescuers must prioritize the mother to protect both lives. The enlarged uterus can compress major blood vessels. For patients beyond 20 weeks, rescuers should use manual left uterine displacement or a 15–30° tilt to improve blood flow while keeping chest compressions effective.

Physiological Changes in Pregnancy Affecting BLS

Pregnancy causes major physiological shifts that affect how Basic Life Support is performed. These changes influence chest mechanics, venous return, airway patency, and oxygen use, so rescuers must adjust standard BLS techniques to maintain maternal and fetal oxygenation. Key physiological changes in pregnancy are as follows:

- The diaphragm elevates by up to 4 cm.

- The rib cage widens and shifts forward.

- Compression hand placement may shift 1–2 vertebral levels higher.

- Effective compression depth may be harder to achieve.

- Blood volume increases by 40%.

- Cardiac output rises by 30–50%.

- Supine positioning can cause aortocaval compression, reducing venous return and cardiac output.

- Oxygen consumption increases by 20%.

- Functional residual capacity decreases by 20%.

- Oxygen desaturation occurs faster during apnea.

- Airway tissues become swollen and more prone to bleeding.

These anatomical, cardiovascular, and respiratory adaptations shape how obstetric emergencies present and guide the modified BLS steps.

Common Emergencies in Pregnant Patients

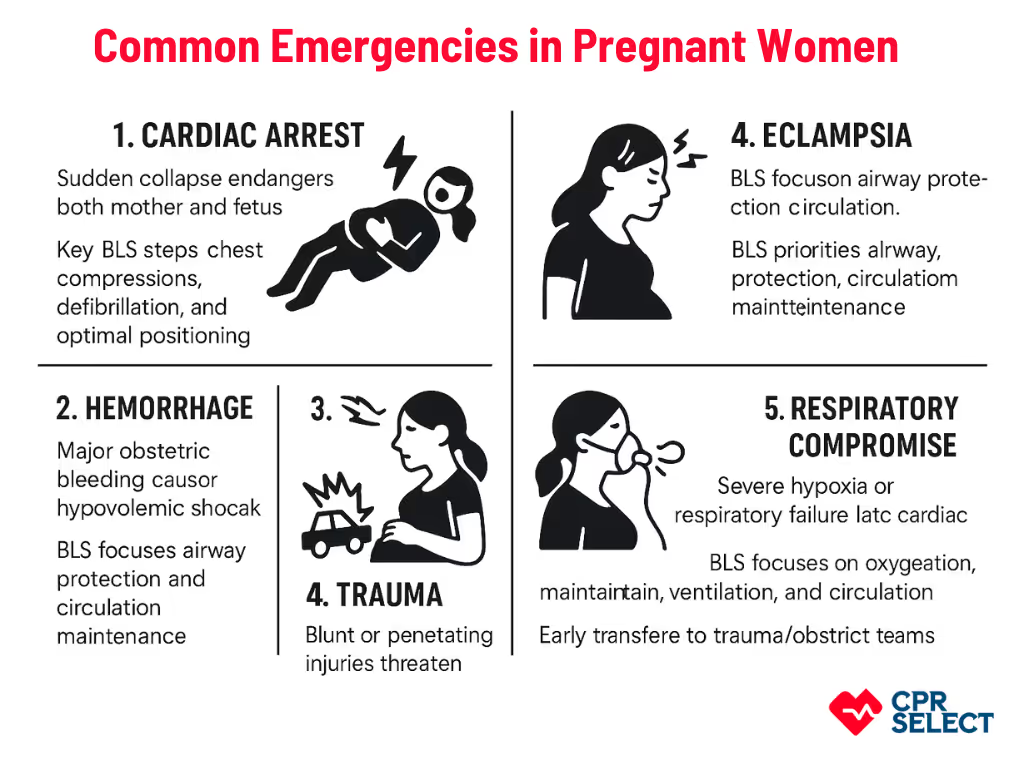

Pregnant patients may face emergencies like maternal cardiac arrest, major obstetric hemorrhage, eclampsia, trauma, and respiratory failure. Each situation presents unique challenges for BLS due to dual-patient considerations, altered maternal physiology, and positional constraints. Rapid recognition and tailored resuscitation are essential to protect both mother and fetus.

1. Cardiac Arrest

Sudden collapse of maternal circulation endangers both mother and fetus. Pregnancy creates a dual-patient scenario and challenges like aortocaval compression, which can reduce venous return by 20–30%. Key BLS steps include high-quality chest compressions (100–120/min, ≥5 cm depth), timely defibrillation, and optimal maternal positioning. If ROSC (return of spontaneous circulation) does not occur within 4 minutes in a viable pregnancy (>20 weeks), perimortem cesarean delivery should be considered within 5 minutes.

2. Hemorrhage

Major obstetric bleeding can cause rapid hypovolemic shock. Immediate priorities include controlling external bleeding, uterine massage if postpartum atony is suspected, preserving circulation and brain perfusion, and activating massive transfusion protocols, while continuing BLS support until definitive care is ready.

3. Eclampsia

Seizures from hypertensive pregnancy disorders can cause sudden loss of consciousness and respiratory compromise. BLS focuses on airway protection, aspiration prevention, left lateral positioning, maintaining circulation, and rapid escalation to critical care. Concurrent management includes magnesium sulfate for seizures and antihypertensives if blood pressure is severely elevated.

4. Trauma

Blunt or penetrating injuries threaten both mother and fetus. Pregnancy-specific considerations include diaphragm displacement, altered anatomy, and potential cervical spine injury. BLS priorities are airway, breathing, and circulation stabilization, spinal precautions, left uterine displacement, and rapid transfer to trauma/obstetric teams.

5. Respiratory Compromise

Severe hypoxia or respiratory failure can lead to cardiac arrest. Pregnancy increases oxygen demand and reduces lung capacity, causing faster desaturation. BLS aims to restore oxygenation, support ventilation, and maintain circulation. Early advanced airway placement and high-flow oxygen are often needed.

Rapid recognition and adapted BLS are critical for all these emergencies. Each condition alters usual resuscitation priorities, and adjustments to chest compressions and positioning are discussed in the next section.